Lieb Robinson Bounds and Many-Body Scars

limits on the spread of information in quantum systems

I had known about Lieb Robinson bounds previously because of the HHKL algorithm

So we consider a local Hamiltonian of the form \(\mathcal{H}=\sum h_x\) defined on \(n\) qubits. We have a Hilbert space with \(2^n\) dimensions such that time evolution of an initial state \(|\psi(0)\rangle\) is given by \(|\psi(t)\rangle=e^{-i\mathcal{H}t}|\psi(0)\rangle\). We are interested in the spread of information in the system. The implementation of such unitaries on a quantum computer is considered efficient if, Unitary \(U\) can be implemented in time \(t\) with a number of gates \(g\) such that \(g\leq poly(n)\) and \(t\leq poly(n)\). The trick is to decompose continuos time evolutions into discrete steps such that discrete steps commute, this is known as Trotterization.

Trotterization example

Let’s say we want to evolve a Hamiltonian given by \(\mathcal{H}=\sum_{i} J(X_{i}X_{i+1} + Y_{i}Y_{i+1}+ Z_{i}Z_{i+1})\) for time \(t\). We can decompose the time evolution into \(N\) steps of size \(\delta t=t/N\) where \(N\) is the number of steps. We can write \(U=e^{-i\mathcal{H}t}\) as \(U=[e^{-i\sum_{i}J\delta t(X_{i}X_{i+1})}e^{-i\sum_{i}J\delta t(Y_{i}Y_{i+1})}e^{-i\sum_{i}J\delta t(Z_{i}Z_{i+1})}]^N\)

Simple example of a Lieb Robinson bound

Consider a simpler example of a electron hopping on a tight binding lattice with nearest neighbour interactions, \(\mathcal{H}=\sum_{n} J(|n\rangle \langle n+1|+|n+1\rangle \langle n|)\). The dispersion relation is given by \(\epsilon_k=-2t\cos{ka}\) where \(k\) is the electron momentum. Hence, the maxmimum group velocity can be derived as \(v_g= \frac{dw}{dk} \leq 2ta\). If we have a 1D lattice, then the maximum speed with which information can spread is \(2ta\). An interesting question to ask is how does a perturbation at one site spread through the lattice. This can be measured by observing the difference between the unperturbed time evolved state \(|\psi(t)\rangle=e^{-i\mathcal{H}t}|\psi(0)\rangle\) with the perturbed state \(|\psi(t)\rangle=e^{-i\mathcal{H}t}e^{-iX_0}|\psi(0)\rangle\).

Many-Body Scars

Before we dive into many-body scar states, it’s essential to understand the broader context of thermalization in quantum systems.

Thermalization in Quantum Systems

In quantum mechanics, thermalization refers to the process where a closed quantum system evolves towards thermal equilibrium. This is typically observed in systems with many degrees of freedom. The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis (ETH) suggests that individual eigenstates of a quantum system at high energy densities are thermal.

Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis (ETH): \(\langle \psi | \hat{O} | \psi \rangle \approx \text{Tr}(\rho_{\text{thermal}} \hat{O}),\) where \(\hat{O}\) is an observable, \(\psi\) is an eigenstate, and \(\rho_{\text{thermal}}\) is the thermal state.

However, not all systems follow the ETH. Two significant exceptions are:

-

Many-Body Localization (MBL): In systems with sufficient disorder, local conserved quantities prevent the system from thermalizing. In MBL systems, eigenstates are non-ergodic.

-

Integrable Systems: These systems have extensively many conserved quantities that prevent them from reaching thermal equilibrium.

Many-Body Scar States

Now, let’s focus on many-body scar states, a relatively recent discovery that presents an exception to typical thermalization behavior. This section is inspired from Fiona Burnell’s talk on many body scar states. I will continue to update it as I read more and more about this exciting topic.

Definition: Many-body scar states are special eigenstates in a non-integrable quantum system that do not thermalize, despite the absence of apparent conserved quantities. These states lead to weak ergodicity breaking.

Characteristics:

-

Prethermalization: The system initially shows signs of thermalization but eventually deviates from it due to the presence of scar states. It is a phase between thermalization and non-thermalization

-

Quantum Recurrences: The system periodically returns to a state close to its initial state.

-

Entanglement Entropy: Scar states exhibit sub-volume law entanglement, unlike typical thermal states that follow a volume law.

Hamiltonian Representation:

Consider a local Hamiltonian \(H\) of a many-body system: \(H \sim c^L \quad \text{(exponentially many thermal eigenstates)},\) where \(L\) is the system size, and \(c\) is a constant. For scar states, the Hamiltonian can be represented as: \(H_{\text{scar}} \sim L^n \quad \text{(polynomially many thermal scar eigenstates)},\) indicating a polynomial number of these special eigenstates.

Entanglement Entropy Calculation:

For a system size \(L\) and a spin \(s\), the Hamiltonian can be represented as: \(H \sim (2s + 1)^L.\) To compute the half-chain entanglement entropy \(S\) for all eigenstates, we use the reduced density matrix (RDM) of a subsystem \(A\): \(S_A = -\text{Tr}(\rho_A \log \rho_A),\) where \(\rho_A\) is the RDM of subsystem \(A\).

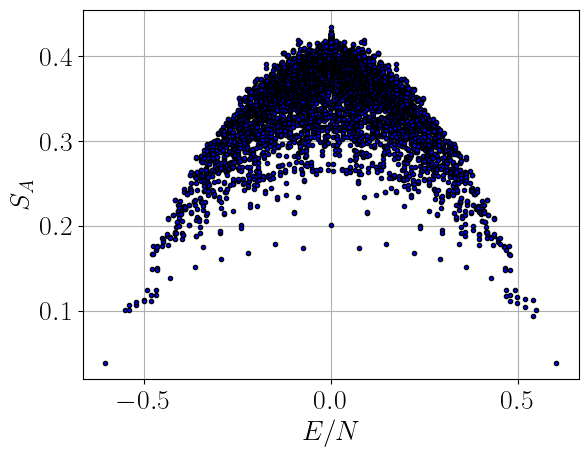

Continuing from our previous discussion on many-body scar states, let’s delve into the specifics of their experimental relevance, structural characteristics, and the significance of Hamiltonian terms in their identification and analysis. Before this let us first see the sub volume law entanglement in scar states. Here I have plotted the entanglement entropy for a system of 18 spins. The entanglement entropy is plotted against the normalized eigenvalue spectrum. We can see that the entanglement entropy is much lower than the thermal entropy for some states. The specific Hamiltonian used here is the PXP model, where \(H=\sum_{i} P_{i-1} X_{i} P_{i+1}\), where \(P_i=\frac{\mathcal{I}-Z}{2}\) is the projector onto the \(i\)th spin being down. The code to generate the plot is given below.

Code to generate the plot above

from quspin.operators import hamiltonian

from quspin.basis import spin_basis_1d # Hilbert space spin basis_1d

from quspin.basis.user import user_basis # Hilbert space user basis

from quspin.basis.user import pre_check_state_sig_32,op_sig_32,map_sig_32 # user basis data types

from numba import carray,cfunc # numba helper functions

from numba import uint32,int32 # numba data types

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import sys, os

quspin_path = os.path.join(os.getcwd(),"../../")

sys.path.insert(0,quspin_path)

N = 18 # total number of lattice sites

#

###### function to call when applying operators

@cfunc(op_sig_32, locals=dict(s=int32,b=uint32))

def op(op_struct_ptr,op_str,ind,N,args):

# using struct pointer to pass op_struct_ptr back to C++ see numba Records

op_struct = carray[op_struct_ptr,1](0)

err = 0

ind = N - ind - 1 # convention for QuSpin for mapping from bits to sites.

s = (((op_struct.state>>ind)&1)<<1)-1

b = (1<<ind)

#

if op_str==120: # "x" is integer value 120 (check with ord("x"))

op_struct.state ^= b

elif op_str==121: # "y" is integer value 120 (check with ord("y"))

op_struct.state ^= b

op_struct.matrix_ele *= 1.0j*s

elif op_str==122: # "z" is integer value 120 (check with ord("z"))

op_struct.matrix_ele *= s

else:

op_struct.matrix_ele = 0

err = -1

#

return err

#

op_args=np.array([],dtype=np.uint32)

#

###### function to filter states/project states out of the basis

#

@cfunc(pre_check_state_sig_32,

locals=dict(s_shift_left=uint32,s_shift_right=uint32), )

def pre_check_state(s,N,args):

""" imposes that that a bit with 1 must be preceded and followed by 0,

i.e. a particle on a given site must have empty neighboring sites.

#

Works only for lattices of up to N=32 sites (otherwise, change mask)

#

"""

mask = (0xffffffff >> (32 - N)) # works for lattices of up to 32 sites

# cycle bits left by 1 periodically

s_shift_left = (((s << 1) & mask) | ((s >> (N - 1)) & mask))

#

# cycle bits right by 1 periodically

s_shift_right = (((s >> 1) & mask) | ((s << (N - 1)) & mask))

#

return (((s_shift_right|s_shift_left)&s))==0

#

pre_check_state_args=None

#

###### construct user_basis

# define maps dict

maps = dict() # no symmetries to apply.

# define op_dict

op_dict = dict(op=op,op_args=op_args)

# define pre_check_state

pre_check_state=(pre_check_state,pre_check_state_args) # None gives a null pointer to args

# create user basis

basis = user_basis(np.uint32,N,op_dict,allowed_ops=set("xyz"),sps=2,

pre_check_state=pre_check_state,Ns_block_est=300000,**maps)

# print basis

print(basis)

#

###### construct Hamiltonian

# site-coupling lists

h_list = [[1.0,i] for i in range(N)]

# operator string lists

static = [["x",h_list],]

# compute Hamiltonian, no checks have been implemented

no_checks=dict(check_symm=False, check_pcon=False, check_herm=False)

H = hamiltonian(static,[],basis=basis,dtype=np.float64,**no_checks)

# compute eigenvalues and eigenvectors

E,V = H.eigh()

# compute entanglement entropy

Sa=np.array([basis.ent_entropy(V[:,i],sub_sys_A=range(N//2))['Sent_A'] for i in range(V.shape[1])])

# use latex for labels

plt.rc('text', usetex=True)

plt.rc('font', family='serif')

plt.rc('font', size=20)

plt.plot(E/N,Sa,'o',markersize=3,markerfacecolor='b',markeredgecolor='k')

plt.xlabel(r'$E/N$')

plt.ylabel(r'$S_A$')

plt.grid(True)Experimental Relevance of Many-Body Scar States

Many-body scar states have garnered significant interest due to their experimental observability and unusual dynamics. A key example is the 2017 experiment by Lukin’s group, which demonstrated these properties

Lukin’s 2017 Experiment

In this experiment, an initially antiferromagnetic configuration, corresponding to a very high temperature, was expected to relax rapidly to a thermal state. However, the observation of long-lived states indicated the presence of many-body scars.

Experiment Observation: \(\text{Initial State: Antiferromagnetic} \implies \text{Expected: Rapid Thermalization} \implies \text{Observed: Long-lived States}\)

This unexpected behavior underscores the importance of understanding scar states, as they can lead to significant deviations from expected thermalization dynamics in quantum systems.

Structural Analysis of Many-Body Scar States

To understand the structure and formation of scar states, we analyze the Hamiltonian of the system, which can be decomposed into three parts: \(H = H_c + H_s + H_a\).

Hamiltonian Components

-

\(H_c\): This term has a non-abelian symmetry, providing a foundational structure for the system.

-

\(H_s\): This term removes degeneracies by assigning different energies to various states, helping isolate the scar states.

-

\(H_a\): A special symmetry-breaking term, \(H_a\) makes the model appear generic away from the scar subspace and is crucial for annihilating all scar states.

Hamiltonian Representation: \(H = H_c + H_s + H_a\)

SU(2) Invariance and Thermal Properties

Consider a system with SU(2) invariance. Due to spin conservation symmetry, the Hamiltonian is divided into multiple blocks. To analyze thermal properties, we focus on individual blocks, noting that some blocks are small and contain approximately \(L\) states.

Block Analysis in SU(2) Invariant System: \(\text{SU(2) Invariance} \implies \text{Multiple Blocks due to Spin Conservation} \implies \text{Analyze Thermal Properties within Each Block}\)

Identifying Scar States

Scar states can be identified as a small multiplet of states isolated by symmetry. The non-generic symmetry-breaking term \(H_a\) plays a crucial role in this process by annihilating these scar states while mixing up all symmetry sectors.

Scar State Identification: \(\text{Candidate Scar States} = \text{Small Multiplet Isolated by Symmetry} \xrightarrow{H_a} \text{Annihilate Scar States, Mix Symmetry Sectors}\)

Symmetry-Breaking and Scar Formation

Scar states arise when symmetry is broken in a non-generic way. Starting with a small corner of the Hilbert space isolated by symmetry, we find terms that break this symmetry but annihilate this specific corner of the Hilbert space.

Symmetry-Breaking Process: \(\text{Start with: Small Corner of Hilbert Space (Isolated by Symmetry)} \xrightarrow{\text{Symmetry Breaking}} \text{Annihilate Corner, Preserve Scar States}\)

Group Invariance in Scar Sectors

In most models, the scar sector is invariant under a “large” group whose rank is proportional to the number of lattice sites. This group is not the symmetry of the Hamiltonian itself. In scar states, the entanglement entropy \(S\) grows logarithmically with the system size \(N\).

Group Invariance: \(\text{Scar Sector Invariance} \leftarrow \text{"Large" Group (Rank} \propto L\text{)}\) \(S \sim \log(N) \text{ in Scar States}\)

to be continued…